A Bow and a Photograph

I’ve always believed that the true magic of community-based tourism lies in the unexpected. It’s not just the places we go—it’s the moments we never planned for, the stories that quietly unfold, and the human connections that make them unforgettable.

My name is Sreejith, and I’m part of Ekathra Experiences. For the past several years, I’ve had the privilege of working alongside various communities across Kerala—particularly indigenous communities whose traditions, resilience, and cultural wisdom continue to teach me something new every day.

A few years ago, we hosted a group of university students from Melbourne, Australia, as part of our experiential learning programme. One of the highlights of their time in Kerala was an interaction we organized in Wayanad with Govindan Ashan, a respected elder from the Kuruma community—a people once known as expert forest dwellers and skilled hunters, masters of the bow and arrow.

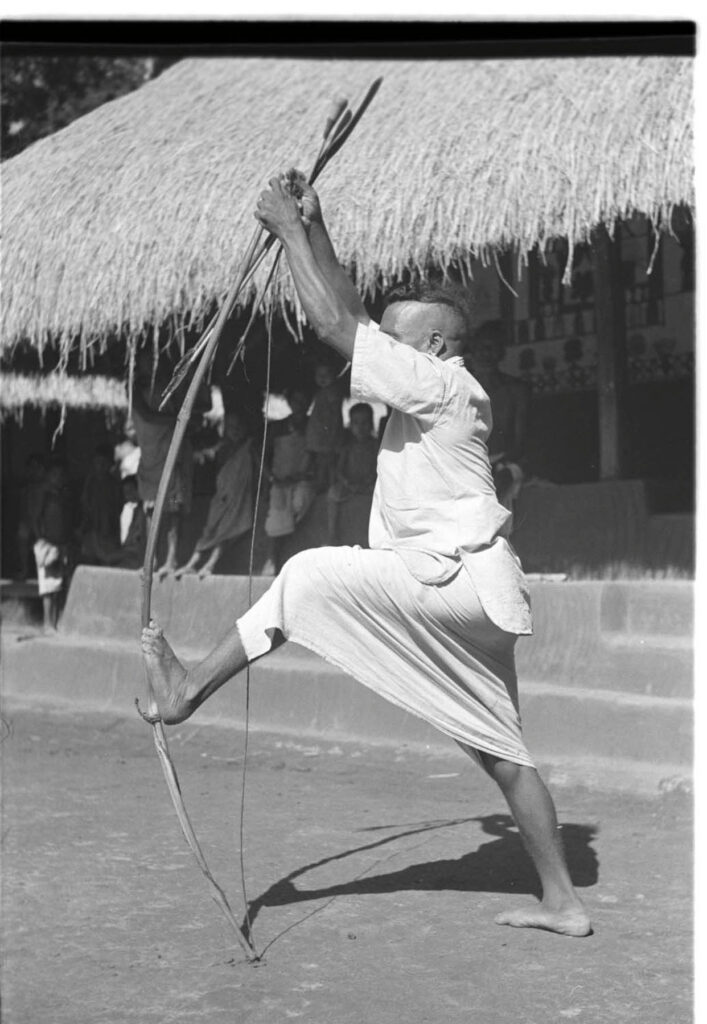

Ashan himself is an exceptional archer. His skill is no longer used in the forests but passed on through coaching and mentorship. Many of his family members—his children and grandchildren—are national-level archery medalists. His humble courtyard is both a training ground and community space, where young people learn not only technique but also pride in their heritage.

But Govindan Ashan is also a gentle soul, deeply connected with the natural world in ways that go beyond archery. Every morning, he feeds hundreds of birds. Parakeets, mynas, bulbuls—wild birds who trust him enough to come daily. A once-hunter turned bird-feeder. The irony isn’t lost on anyone, but in his eyes, it’s not irony—it’s transformation. It’s harmony.

During the students’ visit, they got to try their hand at archery under his guidance. More than just a fun activity, it became a moment of cultural exchange, a chance to appreciate the focus, discipline, and ancestral knowledge behind the craft. Ashan also shared stories from his life—his memories, his love for animals, and his strong belief in conservation.

And then something unexpected happened.

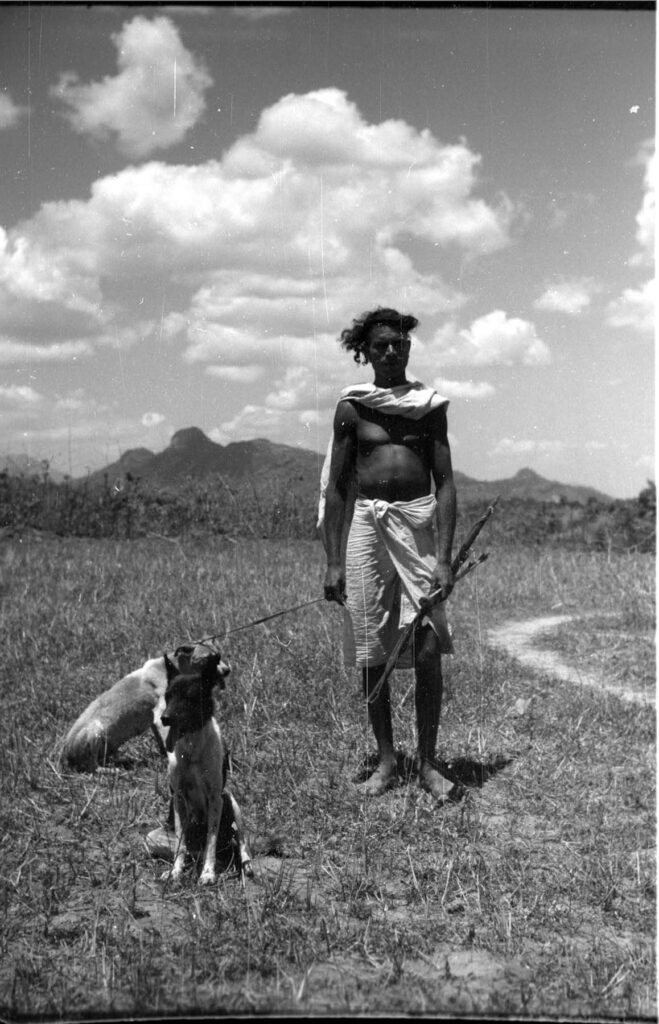

Just as we were wrapping up, one of the faculty members from the student group noticed an old, faded black-and-white photo inside Ashan’s modest home. It showed a Kuruma warrior with a bow, flanked by a loyal-looking dog. She paused in front of it, clearly moved. “I’ve seen this before,” she said, but couldn’t remember where.

Ashan quietly told her: “That’s the only photo I have of my father. He passed away when I was very young.”

The group returned to Australia soon after, but a few weeks later, I received an email from the same faculty member. She had remembered. The photo was from a collection she had come across at a library in Melbourne—part of an old archive of British India, documenting indigenous communities and forest tribes. There were more photos—not just of Ashan’s father, but of other members of the Kuruma community too.

She scanned them and sent them to us.

When we printed them and traveled back to Wayanad to show Ashan, the look on his face said everything. He held the photos with a quiet reverence, touching each one as if it carried a whisper from the past. He thanked us—and her—for bringing his father back to him in a way he never thought possible.

It was a small act. A simple gesture. But it reminded me how community-based tourism is not just about financial support or sustainable practices. It’s about reconnection, about unseen doors opening when people meet with respect, curiosity, and kindness.

We went there expecting to teach students about indigenous archery. Instead, we all learned something far deeper—about heritage, memory, and the unexpected gifts that come when tourism becomes a platform for genuine cultural exchange.

For me, that day wasn’t just a highlight of our program. It was a quiet reminder of why I do this work. Because when we allow learning to flow both ways—when we listen as much as we share—community tourism transforms into something far more powerful. It becomes a space where stories are remembered, identities are honored, and sometimes, long-lost pieces of the past find their way home.